Editor’s Note: The first three installments of the Restoring Sanity series are An Inhuman System, Mental Illness As A Social Construct, and Medicating.

By Susan Hyatt and Michael Carter, Deep Green Resistance

If you don’t want any more anxiety, get rid of all your intelligence and your creativity which would be a very dull life for all of us.

—Rollo May

Don’t worry, be happy.

—Bobby McFerrin

Anxiety is a normal and healthy aspect of human existence. Sören Kierkegaard said, “Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom,” an acknowledgment that we always have some choices to make in life. Each choice we make can bring us closer to our objectives, but can also close off other paths. Choosing is both a birth and a death, both being and non-being. This is why we are anxious. Anxiety begins at the time between being, which is what we experience as a result of our choices, and non-being, which is what we give up. Anxiety is part of becoming, of growing and changing. This is what it means to be alive.

Unhealthy anxiety comes when we are so plagued by worry, stressors, trauma and decisions that we lose tolerance for normal anxiety. We become paralyzed and can no longer act or choose. Thoughts of death may turn to despair and drown out life; we get depressed and apathetic. To be healthily anxious, on the other hand, is in many ways the opposite of depression and apathy. To live a satisfying and effective life is to learn to live with uncertainty. If we become so overwhelmed or intimidated by uncertainty that we avoid making choices, we have passively chosen apathy by default; life then becomes unfulfilling and meaningless. We may walk around and draw breath—feeling like we’re taking action by worrying—but without the opportunities that might have been found by actively choosing. In this way, anxiety and worry become avoidance behaviors that reinforce addictions or depression.

When it’s from fear of life choices or awareness of death, anxiety is not a symptom of a disease but a vigorous mind at work. This is healthy anxiety, finding perspective to make our choices in life or to find appreciation for life in the context of death. In its positive forms, anxiety is meant to motivate us to seek safety, worthiness, competence, and security. Without anxiety, our lives become empty. We wait, not knowing what for, avoiding the unavoidable destiny that comes at the end of our waiting. Healthy anxiety saves us from literal, emotional, and mental death.

Origins

Our previous essays[1] on the oppressive effects of individualism, depression, and addictions all involve an evaluation of the context of civilization. As with any modern mental health problem, a certain sort of anxiety is inherent to living in civilization.

By civilization, we do not mean the supposed social utopia of laws and democratic decisions—a pinnacle of human achievement—that the word has come to mean. Rather we are taking it to task at its root as the formation and maintenance of cities. We define a city as any settlement large enough in population to require the importation of resources.[2] The ancient civilization of Rome was a city that needed to expand its trade influence because it couldn’t grow, log, mine, or otherwise produce its material needs within the city’s immediate area.

While diplomacy and rule of law may play various parts in a civilization’s goals, the underlying requirement will always be force. Because trade is by definition voluntary, Rome’s needs couldn’t be entirely guaranteed by trade alone, so military force had to secure the city within a surrounding empire. Because the environmental and social impacts of agricultural and industrial extraction occur far from a city, it’s possible for civilized people to pretend their way of life is forever sustainable, when in reality it’s the very opposite. The fall of Rome came with the inevitable limits of empire.

To call the Hopi tribe of Arizona a civilization, then, would be false because they had no need to form an empire to acquire what they needed. They had no military because everyone was a warrior,[3] a defender of the high desert they’d made their home for centuries. Calling the Hopi “uncivilized” in the ordinary sense of the word is the worst sort of insult: a lie hidden in a false premise. The Hopi were intelligent, resourceful, fierce, and community-minded, but they were not civilized by the city’s necessity of war and acquisition.

Because nearly all humans alive now were born into civilization, it’s the only reality we know and we naturally take as a given all of its demands. Those include everything from war, deforestation, and global warming, down to the routines of work, money, and worry. Wherever we happen to fit in the wealth-generating scheme of civilization—rich, poor, dominator or oppressed—we assume we’re part of a wise and provident arrangement of humanity.

But civilization is only a destructive imitation of decent human society, a business plan enforced by violence. It is cruel and insane, in denial of the reality of a finite world. Without our knowing it all of civilization’s attributes and consequences have been internalized into our lives, on every level: material, spiritual, and mental. Anxiety, of a chronic and intractable sort, is one of the primary afflictions of the civilized human.

Imagine living in a scrubby, warm forest with a few meandering rivers and rolling meadows, a land so wide it seems to fill the whole of the world. There are no electric lights, no roads, no cars, no computers; only the wild, fecund land. You are a member of an egalitarian society whose food comes from a casual husbandry of small animals like goats and sheep, fishing, the hunting of wild game and gathering of wild plants. Though to a modern person this seems an impossibly distant and antiquated way of life, in fact it was a stable condition that maintained itself very well for many tens of thousands of years.

Agriculture ended that. Not restless inventiveness, not tribal warfare, not human nature, but a technological discovery that made empires possible. Grains can be stored and guarded, and this is what an army really is for, and what it needs more than weapons. As grain cultivation spreads, forests, scrub, and meadows are burned for fields. The grazing animals must go. The rivers must be diverted. The game and predators and wild plants must go, and so food security—for most—must also go. For civilization to produce food surpluses, the majority of people and land area must be enslaved.

The first foundation myth needed for a civilization is that cultivated annuals (wheat, corn, rice) are a more secure food source than hunted or grazed animals. Any monoculture is more prone to catastrophic disease than any polyculture, and requires the constant mining of topsoil to continue. Yet monoculture does produce more food for a limited time, and this allows populations to increase. More people need more food, so more forests fall, and more slaves are born to work more fields.

Generation by generation grain agriculture spread as it consumed topsoil, and agricultural societies adapted to acquire more land. Since their pastoral neighbors hunted, gathered, and fished the lands and waters agriculture needs, they had to go. To continue this way of life, war was no longer about territorial bickering but rather absolute necessity. So was slaving in the fields, and so was the enslavement of women as a resource to produce more slaves, forcing them to increase birthrates.[4] Civilization needs this ongoing control over one by another, and because agriculture requires labor as well as land it will always have many who suffer and toil and few who enjoy the resulting wealth. This social model has grown in sophistication and prevalence, but otherwise hasn’t changed since it began 10,000 years ago.

The Middle East is now stripped of topsoil and human rights and is the hottest furnace of modern war. From what we know about remaining indigenous cultures,[5] life in the pre-agricultural forests of the Fertile Crescent was not the struggle and horror it has become but a comparatively serene existence, with much less work, stress, and illness—physical and mental both. The human animal evolved as a hunting and gathering creature. We are ill-adapted to the civilized life. Its grain-based diet—the malnutrition food of the poor[6]—and constant work schedule keep us literally under the gun, and are the basis for our mental and emotional conditions. Though this condition seems beyond help, it’s not. And it’s here we’ll find answers to why we are always in psychological emergencies.

Anxiety and Culture

The way we experience anxiety is framed by our culture. In civilization, we are conditioned to feel anxiety in relation to competitive ambition. We are trained to compete—in sports, in education, in wealth, in attractiveness, in popularity—and anxiety often results when our unrealistic visions of perfection aren’t reached. Why should security be tied to individual competition? As social animals, we humans have a need for social acceptance and security. Instead of ensuring this, civilization has conditioned us to accept that “winning” brings acceptance and security, and “losing” brings insecurity and social shunning. It is no wonder that anxiety is so pervasive among humans living within the system of civilization. In his book The Meaning of Anxiety, existential psychologist Rollo May writes: “The weight placed upon the value of competitive success is so great in our culture and the anxiety occasioned by the possibility of failure to achieve this goal is so frequent that there is reason for assuming that individual competitive success is both the dominant goal in our culture and the most pervasive occasion for anxiety.”

This competitive arrangement does not reflect a human quality but is rather a means of increasing production and concentrating wealth. Our hunger for security is so strong that those who suffer most from the abuses of a system based on property and coercion will tolerate and even defend the very system that causes their suffering. They will redouble their efforts using the same cultural assumptions, caught in a double bind, having to choose either ambition or poverty.

The more oppressed an individual is within the classes of civilization, the more anxiety they experience and the less likely they are to ever be in an advantaged position to compete. Women and people of color are less likely to be rewarded with high ranking positions because of racism and sex discrimination, which leads to higher rates of anxiety.[7] Success must be glorified, since who wants to compete in a system that is rigged for most of us to lose?

The dominant culture and the social roles into which we are coerced affect the self-esteem or self-worth of women in particular.[8] Women tend to view themselves more negatively than men, which is a major factor for many mental health problems.[9] Psychological disorders in general are 20-40% higher in women than men,[10] and anxiety disorders are most prevalent in women age 16-40.[11] Cognitive distortion[12] is also a symptom of both low self-esteem and pathological anxiety, and comes from living in a culture where economic and social injustice is so normalized as to be nearly invisible. Those on the bottom in this arrangement are the ones who suffer the most, as the powerless are robbed of choices in their own destiny.[13]

As for those who “win” in this system, how can they ever be sure that their competitors won’t gain more wealth and power, possibly at their expense? Even the upper middle class can never obtain absolute security, since they are driven to always increase wealth. It is a vicious cycle of acquisition of power, one that is driven by chronic anxiety and misery.

Definitions

Stress and anxiety have similar effects on our bodies and minds. While either chronic anxiety or stress can disable or kill us, the difference between them becomes more apparent when managing symptoms.[14]

Modern civilized lifestyles burden us with many unavoidable stressors like work, inflexible social rules, and money and health worries. Stress can often be managed by giving the body and mind a rest, assuming one can make the time for it. Healthy lives require relaxation. To sit outside under a shady tree drinking tea and watching butterflies, for example. Stress can be reduced by eating well, exercising, and including enjoyable and healthy activities in our days. Some stress might only be resolved by making major life changes, such as eliminating toxic people from our lives, quitting a stressful job, or moving from a hectic and polluted city. Most people are unable to make these changes, of course, and so are subject to chronic stress, the root problem of many mental and physical health issues.[15]

Anxiety is an unpleasant feeling of nervousness, worry or unease, often about an unknowable outcome or from the fear of being evaluated negatively by others. Specific, acute anxiety keeps us safe from danger and vulnerability. Like pain, anxiety is not a problem itself—both warn us that we need to take some sort of action to reduce or eliminate the cause.

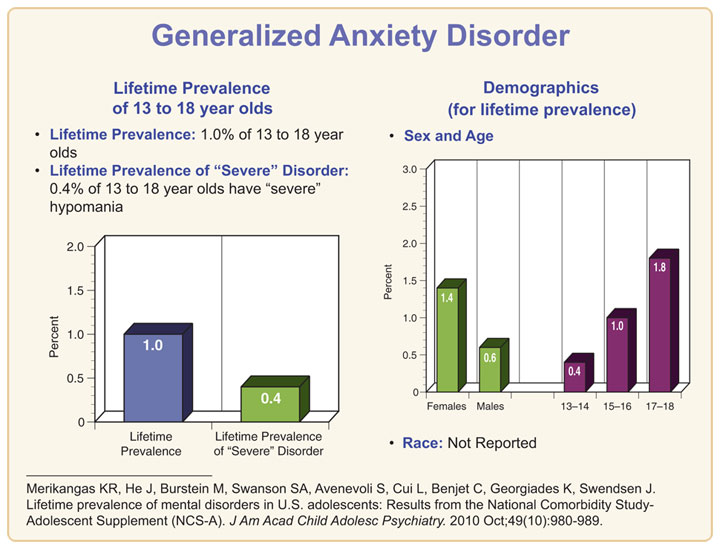

The line between healthy and unhealthy anxiety is vague and subjective. The American Psychiatric Association’s dubiously drug-happy classification handbook, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Volume 5, or DSM-5,[16] recognizes the following diagnosable anxiety disorders: phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety, panic disorder with agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and childhood anxiety disorders.[17] Anxiety disorders are the most common diagnosed mental illnesses in the US, affecting 40 million adults, about 18 percent of the population.[18] According to the National Institute for Mental Health, “Unlike the relatively mild, brief anxiety caused by a stressful event (such as speaking in public or a first date), anxiety disorders last at least 6 months and can get worse if they are not treated.” This is one way of delineating “healthy” from “unhealthy” anxiety. Another way of putting it might be “destructive anxiety” and “constructive anxiety,” though these are subjective terms too.

A more exact definition might be “pathological anxiety,” when danger and vulnerability is exaggerated.[19] If it’s misperceived or nonexistent, there is no action to take that can eliminate the cause of this kind of anxiety, and it can become chronic, generalized, and repressed. Chronic or repressed anxiety leads to apathy, a loss of will, a sense that we can’t obtain anything, and powerlessness. Chronic anxiety can also cause stress that results in physical symptoms like muscle tension, stomach ulcers, heart palpitations, or other physical disorders.[20]

A friend of ours who’s prone to chronic anxiety also has occasional panic attacks, and describes the complete helplessness they bring as “a crazy but certain fear of death.” More mundane moments of anxiety, he says, are more about an inability to perform the simplest tasks. “It’s hard for me to tell the difference between apathy and anxiety,” he explains. We the authors are a more fidgety breed, using anxiety as an engine of activity that often gets so out of control that relaxation is impossible, and our only rest comes from exhaustion. In its most extreme form, this constant stress probably led to Hyatt’s life-threatening autoimmune disorder.

What about positive thinking?

A well-meaning person, concerned about our pain over suffering and injustice, suggested: “What do you think of cultivating a mind where there is a peaceful separation of thought from emotional response?” This seems like a practical idea, encouraged by titles of self-help books like Anxiety Free: Stop Worrying and Quiet Your Mind, and of course it isn’t helpful to get upset about every sad or awful thing the dominant culture does to innocent beings. For one thing, that list is so terribly long; for another, emotions amount to little until they are engaged with action and there is only so much anyone can do, no matter how dedicated they are. But separating our emotional responses from our physical and mental experiences creates disconnection with reality and ourselves. The same is true of undiscriminating negativity.

Is it only by dissecting ourselves (mind from body, emotion from reason, thought from feeling) that we can live a decent life in a civilized world? This is like separating emotional knowledge that the earth is alive from practical knowledge of the minerals in its crust. The ore can be extracted and we don’t feel bad about it. We can then continue on with the lie that we are free. The well-being of our wider community, which must include other species, other cultures, whole biomes, is more important than our personal sense of peace. This is because any lasting freedom and peace—personal or otherwise—depends on functional communities (human and nonhuman both) to exist. It is a sign of our oppression that we must resort to positive thinking to avoid the need to engage a negative but healthy response to living in an unsustainable, toxic society.

When we react with anxiety to situations that we can neither eliminate nor attenuate, it does seem as if the only relief is to think positive thoughts or to feel nothing at all. Chemicals like alcohol and psychiatric meds can help this numbing; so can religion and spirituality. Avoiding the truth might eliminate anxiety or stress in the short term, but the global effects of civilization (deforestation, climate destabilization, ocean acidification, mass extinction, etc.[21]) are neither exaggerations nor the creations of our minds. It would not be healthy—or even rational—to try to cultivate a peaceful, unemotional mind and think positive thoughts when the living world is dying.[22] Avoidance behavior is one reason for this dying; it is also the core of depression, pathological anxiety, and many other disorders that define poor mental and emotional health.

Remedies

The long-term social solution to chronic stress and anxiety is to dismantle civilization and the toxic society resulting from this way of life, and to restore healthy landbases and human communities. Personal solutions for anxiety problems are also available, though they may seem no less daunting.

Remedies for the pathological anxiety of agricultural societies arose alongside the causes. Monotheistic religions are perhaps the best example. Their promotion of controlling behavior, unavoidable apocalypses, and the primary importance of individual salvation all serve the needs of empires. Even Taoism, among the least warlike of civilized doctrines, emphasizes the detachment from the real world that war requires. If starvation is a terrifying reality—as it surely was and will continue to be for many Chinese—it’s no surprise that such a belief system would evolve. Nor is it surprising that women might come to be hated by cultures driven to control their environment—such as those based on agriculture. Treating women as objects to extract resources from grows logically out of this type of culture, as does male violence towards women.

Durable solutions to human misery won’t be found in the usual responses of victim blaming, resource exploitation, and promising rewards in the afterlife, as civilized societies have always done. This is true on both a social and personal scale. Modern pharmaceuticals[23] are only another way civilization moderates its hurtful effects on humans. Helpful as psychiatric meds may occasionally be, they are not fundamentally different than Marx’s “opiates of the masses” or the many cheap and emotionally damaging distractions of pageantry and spectacle for sale anywhere one cares to look. They’re all coping mechanisms engineered within systems of control that have the system’s needs in mind, not ours.

Denial of emotion is necessary for the dominant culture to function, and complements the way civilization treats every living being as an object. Yet we are alive, and we do feel. So what are we to do with all that worry and stress, if we don’t separate our emotional responses from our daily exposure to the cruelty and waste that civilization requires? Will we despair? Or even worse for civilization, work to take it down because it hurts so much? Will we find others who feel similarly, and organize to resist the destruction of the world and all that’s in it? In the meanwhile, how do we cope with our own worries? Awareness of circumstances and our reactions is a critical first step to healing.

A good way to begin might be to shrink the immensity of the problem to manageable parts, so we might get some short-term relief. When experiencing anxiety, it is essential to analyze the cause to determine if it can be eliminated. This might be as simple as finishing a difficult homework assignment or taking the next step towards completing a big project. If the source of anxiety cannot be eliminated or reduced, we may need to take steps to change how we feel. Some effective non-drug treatments are eliminating caffeine and alcohol, improving diet, and supplementing B and D vitamins. Our friend with panic attacks notes that these steps alone usually eliminate all sensations of pathological anxiety. Other helpful methods include psychotherapy, meditation, self-hypnosis, yoga, and various thought-stopping techniques.[24] These all involve a lot of trial and error, so it’s important to remember that failures do not reflect on who we are; they are rather only events, part of discovering, learning, evolving and adapting.

Anxiety has a positive and healthy aspect, and is not to be avoided. The constructive use of anxiety is how we create satisfying and effective lives, and perhaps influence the future of the world in a positive way. Anxiety is inseparable from love. When we love, we commit ourselves to action. Love is the motivation for social and environmental activism, for taking on responsibility, for finding ways to influence our society and world. Anxiety is experienced as a possibility, the intermediate between potential and reality; it connects us to the world and drives us to protect those we love.

All these problems we now face, it’s no wonder that this is an anxious age because all these things, overpopulation, pollution are going on all at once… Now these things are all symptoms of what makes this an anxious age and I think that what we must do as far as we can is to shift our thinking from simply worrying about these different problems to the questions of what can we do about them? The point is to turn your anxiety into active affect, to overcome the situation.

—Rollo May

Susan Hyatt has worked as a project manager at a hazardous waste incinerator, owned a landscaping company focused on native Sonoran Desert plants, and is now a volunteer activist. Michael Carter is a freelance carpenter, writer, and activist. His anti-civilization memoir Kingfisher’s Song was published in 2012. They both volunteer for Deep Green Resistance Southwest Coalition.

Bibliography and Further Reading

American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

Beck, Aaron T., and Emery, Gary. Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective. New York: Basic Books, 1985.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking in Undermining America. New York: Picador, 2009.

Friedman, Ariellad and Todd, Judith. “Kenyan Women Tell a Story: Interpersonal Power of Women in Three Subcultures in Kenya.” Sex Roles 31: 533-546, in Nanda, Serena and Warms, Richard L. Cultural Anthropology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson, 2004, 387, 388.

Jensen, Derrick, Endgame Volume I: The Problem of Civilization, New York City, NY: Seven Stories Press, 2006.

Keith, Lierre. The Vegetarian Myth. Crescent City, CA: Flashpoint Press, 2009.

Leventhal, Allan M. and Martell, Christopher R. The Myth of Depression as Disease: Limitations and Alternatives to Drug Treatment. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2006.

Manning, Richard. Against the Grain: How Agriculture has Hijacked Civilization. New York: North Point Press, 2004.

May, Rollo. Freedom and Destiny. New York: WW Norton and Company, 1981.

_____. Love and Will. New York: Delta, 1989.

_____. The Meaning of Anxiety, Revised Edition. New York: WW Norton and Company, 1977.

Maybury-Lewis, David. Millennium: Tribal Wisdom and the Modern World. New York: Viking Penguin, 1992.

McKay, Matthew, Ph.D., and Fanning, Patrick. Self Esteem. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger, 2000.

Sevillano, Mando. The Hopi Way: Tales from a Vanishing Culture. Flagstaff, AZ: Northland Press, 1986.

Online

Awais Aftab, MD, MBBS, “Mental Illness vs Brain Disorders: From Szasz to DSM-5,” Psychiatric Times, February 28, 2014, http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/dsm-5-0/mental-illness-vs-brain-disorders-szasz-dsm-5#sthash.hA4QwWSp.wptbyJ4M.dpuf

James Ball, “Women 40% more likely than men to develop mental illness, study finds,” The Guardian, May 22, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/may/22/women-men-mental-illness-study

Thomas B. Bramanti, W. Haak, M. Unterlaender, P. Jores, K. Tambets, I. Antanaitis-Jacobs, M.N. Haidle, R. Jankauskas, C.-J. Kind, F. Lueth, T. Terberger, J. Hiller, S. Matsumura, P. Forster, and J. Burger, “Genetic Discontinuity Between Local Hunter-Gatherers and Central Europe’s First Farmers,” Science 2009, as reported in Science Daily, September 4, 2009, http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/09/090903163902.htm

Levine, Bruce E., “Psychiatry Now Admits It’s Been Wrong in Big Ways—But Can It Change?” Truthout, March 5, 2014, http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/22266-psychiatry-now-admits-its-been-wrong-in-big-ways-but-can-it-change

Moore, Heidi, “Little surprise here: women expected to do more at home—and at work,” The Guardian, November 1, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/nov/01/women-work-harder-favors-never-counted?CMP=twt_gu

Nauert, Rick, PhD., and Grohol, John M., Psy.D., “Beyond Antidepressants: Taking Stock of New Treatments,” Psych Central, February 18, 2014, http://psychcentral.com/news/2014/02/18/beyond-antidepressants-taking-stock-of-new-treatments/66071.html

Endnotes

[1] Susan Hyatt and Michael Carter, “Restoring Sanity, Part 1: An Inhuman System,” Deep Green Resistance Southwest Coalition, February 6, 2014, http://deepgreenresistancesouthwest.org/2014/02/06/restoring-sanity-part-1-an-inhuman-system/

Susan Hyatt and Michael Carter, “Restoring Sanity, Part 2: Mental Illness as A Social Construct,” Deep Green Resistance Southwest Coalition, March 13, 2014, http://deepgreenresistancesouthwest.org/2014/03/13/restoring-sanity-part-2-mental-illness-as-a-social-construct/

Susan Hyatt and Michael Carter, “Restoring Sanity, Part 3: Medicating,” Deep Green Resistance Southwest Coalition, May 20, 2014, http://deepgreenresistancesouthwest.org/2014/05/20/restoring-sanity-part-3-medicating/

[2] “Civilization is a culture—that is, a complex of stories, institutions, and artifacts—that both leads to and emerges from the growth of cities (civilization, see civil: from civis, meaning citizen, from Latin civitatis, meaning city-state), with cities being defined—so as to distinguish them from camps, villages, and so on—as people living more or less permanently in one place in densities high enough to require the routine importation of food and other necessities of life.” Jensen, 17.

[3] Sevillano, 38.

[4] Manning, 36.

Birthrates increased by a factor of four.

[5] Maybury-Lewis.

Millennium is an excellent, general reference on the comparative ease of hunting and gathering life, and an accessible introduction to the academic field of cultural anthropology. The book and accompanying film series describe several noncivilized cultures around the world, their customs and beliefs and general temperament. Chapter 2, “An Ecology of Mind,” (pages 35-62) is especially illuminating.

[6] John B. Marler and Jeanne R. Wallin, “Human Health, the Nutritional Quality of Harvested Food and Sustainable Farming Systems,” Nutrition Security Institute, 2006, accessed November 10, 2014, http://www.nutritionsecurity.org/PDF/NSI_White%20Paper_Web.pdf

[7] Mallory Bowers, “(en)Gendering psychiatric disease: what does sex/gender have to do with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?” The Neuroethics Blog, May 6, 2014, http://www.theneuroethicsblog.com/2014/05/engendering-psychiatric-disease-what.html

[8] “It’s certainly plausible that women experience higher levels of stress because of the demands of their social role – with that stress helping to trigger problems like anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and insomnia. Increasingly, women are expected to function as carer, homemaker, and breadwinner – all while being perfectly shaped and impeccably dressed. Given that domestic work is undervalued, and considering that women tend to be paid less, find it harder to advance in a career, have to juggle multiple roles, and are bombarded with images of apparent female ‘perfection’, it would be surprising if there weren’t some emotional cost.

“It’s worth remembering too that women are also much more likely than men to have experienced childhood sexual abuse, a trauma that all too often results in lasting psychological and emotional damage,” Daniel Freeman, Ph.D. and Jason Freeman , “Know Your Mind” Psychology Today, June 2013, http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/know-your-mind/201306/the-stressed-sex-1

[9] James Ball, “Women 40% more likely than men to develop mental illness, study finds,” The Guardian, May 22, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/may/22/women-men-mental-illness-study

[10] Daniel Freeman and Jason Freeman, “Let’s talk about the gender differences that really matter – in mental health”, The Guardian, Dec 13, 2013 http://www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2013/dec/13/gender-differences-mental-health

[11] Beck and Emery, 83.

[12] McKay and Fanning, 61-87

[13] “In one study, researchers used a storytelling technique to evaluate three groups of Kenyan women: rural women in a traditional village, poor urban women, and middle-class urban women…traditional women almost always told very positive stories that usually had a happy ending. Middle-class urban women told stories that emphasized their own power and competence. Poor urban women’s stories were generally tragic and focused on powerlessness and vulnerability. The researchers note that many poor urban women have ‘lost the security and protection of the old [traditional] system without gaining the power or rewards of the new system,’” Friedman and Todd.

[14] “Chronic anxiety and chronic stress often share a lot in common. They have similar emotional symptoms, they result in similar physiological reactions, and can easily be confused with the other. In a fast paced world, experiencing stress and anxiety is common and frequently people experience them simultaneously; however, it is important to understand the etiology of the symptoms and luckily there are differences which can help tell them apart. Chronic anxiety sufferers who have experienced therapy are often aware of their triggers…” Michele L. Brennan, Psy.D, “Is It Anxiety or Stress?” Psych Central, accessed October 2, 2014, http://blogs.psychcentral.com/balanced-life/2014/01/is-it-anxiety-or-stress/

[15] “The long-term activation of the stress-response system—and the subsequent overexposure to cortisol and other stress hormones—can disrupt almost all your body’s processes. This puts you at increased risk of numerous health problems, including: Anxiety, depression, digestive problems, heart disease, sleep problems, weight gain, and memory and concentration impairment.” “Chronic stress puts your health at risk,” Mayo Clinic, accessed October 14, 2014, http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-living/stress-management/in-depth/stress/art-20046037

[16] We discuss the primacy of medications in modern psychiatric care more thoroughly in the second essay in this series, “Restoring Sanity, Part 2: Mental Illness as A Social Construct,” http://deepgreenresistancesouthwest.org/2014/03/13/restoring-sanity-part-2-mental-illness-as-a-social-construct/

[17] Cara Santa Maria, “Anxiety vs. Stress: What’s The Difference?” Huffington Post, September 20, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/12/15/anxiety-stress-difference_n_1152590.html

American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Ed.).

[18] “Anxiety Disorders,” National Institute for Mental Health, accessed October 6, 2014, http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml

[19] Beck and Emory, 30, 68.

[20] “When the individual is burdened with anxiety over a long period of time and he feels he can’t do anything about it, then he may develop not only physical tension but he may develop physical symptoms—they may be heart palpitations or gastric ulcers or some other kind of physical symptom.” Rollo May, “Understanding and Coping with Anxiety,” Society for Existential Analysis, republished from Psychology Today, 1978, http://www.existentialanalysis.org.uk/assets/articles/Understanding_and_Coping_with_Anxiety_Rollo_May_transcription_Martin_Adams.pdf

[21] “Indicators of Ecological Collapse,” Deep Green Resistance, accessed October 1, 2014, http://deepgreenresistance.org/why-resist/ecological-collapse

[22] Madhusree Mukerjee, “Apocalypse Soon: Has Civilization Passed the Environmental Point of No Return?” Scientific American, May 23, 2012, http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=apocalypse-soon-has-civilization-passed-the-environmental-point-of-no-return

“Species Disappearing at an Alarming Rate, Report Says. Watchdog Releases Annual ‘Red List,’ Warns Extent is Underestimated,” MSNBC.com, November 17, 2004, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6502368/ns/us_news-environment/t/species-disappearing-alarming-rate-report-says/#.T06Tsnn8l2I

[23] “Fluoxetine (Prozac®), sertraline (Zoloft®), escitalopram (Lexapro®), paroxetine (Paxil®), and citalopram (Celexa®) are some of the SSRIs commonly prescribed for panic disorder, OCD, PTSD, and social phobia. SSRIs are also used to treat panic disorder when it occurs in combination with OCD, social phobia, or depression. Venlafaxine (Effexor®), a drug closely related to the SSRIs, is used to treat GAD. These medications are started at low doses and gradually increased until they have a beneficial effect.” National Institute for Mental Health, “Anxiety Disorders,” accessed October 27, 2014, http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml#pub8

[24] Michele L. Brennan, Psy.D, “Is It Anxiety or Stress?” Psych Central, accessed October 2, 2014, http://blogs.psychcentral.com/balanced-life/2014/01/is-it-anxiety-or-stress/.

I suffer from a profound sense of loneliness. I always have. I do not know why. And, I suspect I always will. Sometimes, I wonder if I cling to some strange addiction to loneliness. There are too many decisions I’ve made in my life knowing full well the alienation that would follow.

I suffer from a profound sense of loneliness. I always have. I do not know why. And, I suspect I always will. Sometimes, I wonder if I cling to some strange addiction to loneliness. There are too many decisions I’ve made in my life knowing full well the alienation that would follow.

For the last year, it goes like this: My phone rings precisely at 6:30 AM. I groan in bed and reach towards the shelf holding my phone. By the time I locate my phone, I’ve missed the call. It’s from an area code I don’t recognize. They’ve left a message, so I curse, roll over, cuddle a pillow to my chest, and fall back asleep. When I wake up there are three more calls from three different area codes with three more messages. I listen to the messages.

For the last year, it goes like this: My phone rings precisely at 6:30 AM. I groan in bed and reach towards the shelf holding my phone. By the time I locate my phone, I’ve missed the call. It’s from an area code I don’t recognize. They’ve left a message, so I curse, roll over, cuddle a pillow to my chest, and fall back asleep. When I wake up there are three more calls from three different area codes with three more messages. I listen to the messages.

It’s been 13 months since the sun and stones helped me make sense of my two suicide attempts. I have not tried to kill myself since. This is not to say that I’m completely recovered. I still think about suicide. Suicide is a smooth-voiced monster lurking just below the surface of still, warm waters.

It’s been 13 months since the sun and stones helped me make sense of my two suicide attempts. I have not tried to kill myself since. This is not to say that I’m completely recovered. I still think about suicide. Suicide is a smooth-voiced monster lurking just below the surface of still, warm waters.

So far, my writing in this Do-It-Yourself Resistance series has focused on the emotional and spiritual conditions that I believe would-be resisters must find as they begin their path to saving the world.

So far, my writing in this Do-It-Yourself Resistance series has focused on the emotional and spiritual conditions that I believe would-be resisters must find as they begin their path to saving the world.