Protect Pinyon-Juniper Forests Campaign

Deep Green Resistance and WildLands Defense are advocating for a moratorium on all pinyon-juniper deforestation in the Great Basin and we need your help. Pinyon-juniper forests are being wantonly killed as weeds while their inherent ecological value is summarily ignored. These forests store carbon dioxide, dampen climate change, provide crucial wildlife habitat, protect watersheds, and have helped humans survive in the Great Basin for millennia. A moratorium gives us time to marshall our resources to put this destruction to a permanent end.

See for yourself the destruction of Pinyon-Juniper forests and then join the fight.

Don’t let them destroy these forests! Sign our petition here.

Also join us to ask BLM to stop clearcutting pinyon-juniper forests.

3/25/2016 The Language of Pinyon-Juniper Trees

2/3/2016 BLM & the Ranching Industry: a History of Collusion

1/5/2016 Pinyon-Juniper Forests: BLM’s False Claim to Virtue

12/13/2015 Pinyon-Juniper Forests: The Oldest Refugee Crisis

12/1/2015 Pinyon-Juniper Forests: An Ancient Vision Disturbed

Follow our Protect Pinyon-Juniper Forests campaign on Facebook for more updates.

Sacred Waters, Sacred Forests

A Gathering for Celebration, Community, Movement Building, Ecology, and Land Defense

Join us in May of 2016 for a tour of sacred lands threatened by the proposed Southern Nevada Water Authority groundwater pipeline. We will spend three days visiting the communities affected by the water grab, learning about the project and the threatened sacred lands and waters. For those already familiar, we’ll also be holding workshops on the ecology and politics of the region at a basecamp in Spring Valley. The tour will begin at Cleve Creek campground, 12 miles north of Highway 6-50 at the base of the Schell Creek Mountains.

The SNWA water grab is a prime example of how civilizations (cultures based on cities, as opposed to cultures based on perpetual care of their landbases, without resource drawdown) inevitably destroy the planet. A bloated power center, ruled by the ultra-rich and served by an underclass of poorly-paid workers, bolstered by bought-and-paid-for politicians (see Harry Reid) and misused public tax dollars, reaches out and takes what it wants from the countryside.

One of the developers who wants the water grab has described the Mojave desert around Las Vegas as “flat desert stuff.” They call living land a wasteland to justify its continuing plunder. To indigenous peoples—Shoshone, Paiute, and Goshute—the land and water are sacred.

Anyone who respects land and visits this place will fall in love with it. That’s the purpose of the Sacred Water Tour, an annual gathering organized by Deep Green Resistance for the past three years. In coordination with local activists and indigenous people, the public is welcomed every Memorial Day weekend to tour the region.

Resistance Radio: Derrick Jensen interviews Max Wilbert about the SNWA water grab

2015 Sacred Water Tour: Sacred Water Under Threat

2014 Sacred Water Tour: Report-Back

Groundwater Pipeline Threatens Great Basin Desert, Indigenous Groups

Follow our Stop the SNWA Water Grab campaign page on Facebook for more updates

Regional News

Follow the DGR Southwest Coalition Facebook page for more news.

Deep Green Resistance News Service Excerpts

Derrick Jensen: When I Dream of a Planet In Recovery

The time after is a time of magic. Not the magic of parlor tricks, not the magic of smoke and mirrors, distractions that point one’s attention away from the real action. No, this magic is the real action. This magic is the embodied intelligence of the world and its members. This magic is the rough skin of sharks without which they would not swim so fast, so powerfully. This magic is the long tongues of butterflies and the flowers who welcome them. This magic is the brilliance of fruits and berries who grow to be eaten by those who then distribute their seeds along with the nutrients necessary for new growth. This magic is the work of fungi who join trees and mammals and bacteria to create a forest. This magic is the billions of beings in a handful of soil. This magic is the billions of beings who live inside you, who make it possible for you to live.

Derrick Jensen: Not In My Name

Let me say upfront: I like fun, and I like sex. But I’m sick to death of hearing that we need to make environmentalism fun and sexy. The notion is wrongheaded, disrespectful to the human and nonhuman victims of this culture, an enormous distraction that wastes time and energy we don’t have and undermines whatever slight chance we do have of developing the effective resistance required to stop this culture from killing the planet. The fact that so many people routinely call for environmentalism to be more fun and more sexy reveals not only the weakness of our movement but also the utter lack of seriousness with which even many activists approach the problems we face. When it comes to stopping the murder of the planet, too many environmentalists act more like they’re planning a party than building a movement.

Sustaining a Strategic Feminist Movement

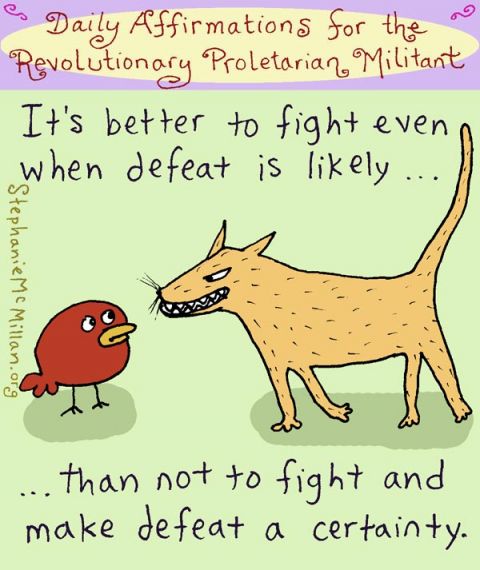

At the core of this movement, there is an intangible force with a measurable impact. It’s an attitude, a mindset, a determination that compels us to push back against oppression. It’s the warrior mindset, the stand-and-fight stance of someone defending her home and the ones she loves.

Many burn with righteous anger. This is important – anger lets us know when people are hurting us and the ones we love. It’s part of the process of healing from trauma. Anger can rouse us from depression and move us past denial and bargaining. It is a step toward acceptance and taking action.

Rewriting the trauma script includes asserting our truth and lived experiences, and naming abuses instead of glossing over them. It includes discovering (and rediscovering) that we can rely on each other instead of on men. It’s mustering the courage to confront male violence. But it’s not going to be easy.

Ben Barker: Masculinity is Not Revolutionary

To be masculine, “to be a man,” says writer Robert Jensen in his phenomenal book, Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity, “…is a bad trade. When we become men—when we accept the idea that there is something called masculinity to which we could conform—we exchange those aspects of ourselves that make life worth living for an endless struggle for power that, in the end, is illusory and destructive not only to others but to ourselves.” Masculinity’s destructiveness manifests in men’s violence against women and men’s violence against the world. Feminist writer and activist Lierre Keith notes, “Men become ‘real men’ by breaking boundaries, whether it’s the sexual boundaries of women, the cultural boundaries of other peoples, the political boundaries of other nations, the genetic boundaries of species, the biological boundaries of living communities, or the physical boundaries of the atom itself.”

Too often, politically radical communities or subcultures that, in most cases, rigorously challenge the legitimacy of systems of power, somehow can’t find room in their analysis for the system of gender. Beyond that, many of these groups actively embrace male domination—patriarchy, the ruling religion of the dominant culture—though they may not say this forthright, with claims of “anti-sexism.” Or sexism may simply not ever be a topic of conversation at all. Either way, male privilege goes unchallenged, while public celebrations of the sadism and boundary-breaking inherent in masculinity remain the norm.

Film Review: The Wind that Shakes the Barley

All people interested in a living planet–and the resistance movement it will take to make that a reality–should watch this film. The courage found within every one forming their amazing culture of resistance–militant and non; including those who set up alternative courts, sang traditional songs and speak the traditional Gaelic language, open their homes for members of the resistance–is more than i have ever experienced, yet exactly what is needed in our current crisis. Those who fought back endured torture, murder, and the destruction of their communities. Yet, they still fought because they were guided by love and by what is right.

Deep Green Resistance: a quote from the book

In blunt terms, industrialization is a process of taking entire communities of living beings and turning them into commodities and dead zones. Could it be done more “efficiently”? Sure, we could use a little less fossil fuels, but it still ends in the same wastelands of land, water, and sky. We could stretch this endgame out another twenty years, but the planet still dies. Trace every industrial artifact back to its source which isn’t hard, as they all leave trails of blood-and you find the same devastation: mining, clear-cuts, dams, agriculture. And now tar sands, mountaintop removal, wind farms (which might better be called dead bird and bat farms). No amount of renewables is going to make up for the fossil fuels or change the nature of the extraction, both of which are prerequisites for this way of life. Neither fossil fuels nor extracted substances will ever be sustainable; by definition, they will run out. Bringing a cloth shopping bag to the store, even if you walk there in your Global Warming Flip-Flops, will not stop the tar sands. But since these actions also won’t disrupt anyone’s life, they’re declared both realistic and successful.

![pija_5910c[3]](/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2015/12/pija_5910c3.jpg)

And just as matter can neither be created nor destroyed, when you and your land base engage in the mutual sharing of bodies trading processes, materials, and spirit in the holiest of intercourses, you can never truly leave that land base and that land base can never truly leave you.

And just as matter can neither be created nor destroyed, when you and your land base engage in the mutual sharing of bodies trading processes, materials, and spirit in the holiest of intercourses, you can never truly leave that land base and that land base can never truly leave you.